Bill Plympton, the American graphic designer and cartoonist, who around 30 years ago chose the path of animated film and became a legend in this artistic and amusing, but highly competitive field, was the big guest star of the 13th edition of Vienna Independent Shorts.

The festival even broke one of its rules and screened a feature film, his “most outrageous work” as he says himself, I Married a Strange Person!, about a man who can permutate his reality. During the festival we had the opportunity to get up close and personal with the artist and his animated permutations, through screenings, a masterclass and an interview for Nisimazine.

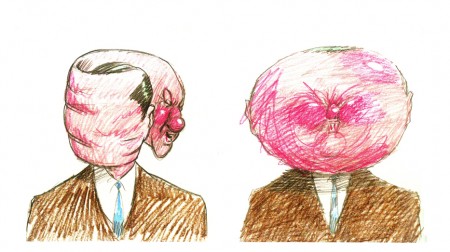

The always very casually dressed and easy-going Plympton, playful even at the tender age of 70, isn’t famous because of the awards he either won or was nominated for, but because of his wicked sense of humour at animating adult issues and “deadly sins”, like lust and revenge. This combination earned him a cult following, including like-minded reality-benders Terry Gilliam and Quentin Tarantino. His films are full of metamorphoses, wild camera movements and grotesque, violent, provocative, bizarre, politically incorrect and tongue-in-cheek narratives.

"Negotiating with Disney is not so much good cop – bad cop, it's more like bad cop – antichrist."

But it was the Disney Studios that played a crucial role for the development of his art. Although even back home in Oregon he used to draw on every surface that allowed it, the pivotal moment came when, as a child, he discovered Disney cartoons on TV. They made him laugh and at the same time convinced him to become an animator and seek a position at the Studio. When he was 15 or 16, he applied and got rejected as talented, but too young.

It took the studio almost 25 years to get back to him and this time it was he who turned them down. After he earned his first of so far two Oscar® nominations in 1988 for his animated short film Your Face (the second followed in 2005 for Guard Dog), they wanted to hire him for an undefined film, which later turned out to be Aladdin. Although they offered him $1 million, the studio didn’t want to grant him the freedom to retain ownership over his personal side projects. As he explained:

“Negotiating with Disney is not so much good cop – bad cop, it’s more like bad cop – antichrist. […] So I said no. Sometimes I wonder if that was such a good idea. But I just think I would have gotten tired of the restrictions, bureaucracy and formality of working at a Disney studio. Even though when I was a kid that was my dream, to be a Disney animator. But there is something about waking up every morning, going to my drawing board, draw whatever the hell I want and nobody is saying ‘no, you can’t draw that’. And to me that’s worth more than a million bucks.”

He decided to quit his print work and concentrate solely on animations.

Before choosing animated film as his channel of expression, Plympton was a cartoonist for publications, for example Playboy, Penthouse,Vanity Fair, as well as a graphic designer. As he was working on a booklet, he got the offer to make an animated film. After learning the laws of the trade, he made Boomtown, a rarely shown film he dislikes as “crude and overly political”. Nevertheless, it was successful and introduced him to the film festival circuit, where he met fellow animators and got inspired by them.

His new career reached a first peak with Your Face, a musical film with silly lyrics. Yet through the laughter of the audiences, growing respect from colleagues, worldwide fame, and the Oscar® nomination, it was such an uplifting, profitable and successful experience, that he made a decision: he decided to quit his print work and concentrate solely on animations.

"Plympton Dogma": films have to be short, cheap and funny in order to make money.

“I called up all my print clients and I said I’m quitting print and I’m going into animation. And they laughed at me.”

Little did they know…

He calls the secret of his success the “Plympton Dogma”. According to it, films have to be short, cheap and funny in order to make money. Animators have to constantly accumulate and develop ideas in a broader as possible personal union – as directors, producers, writers, editors – and stay away from longer forms (he opts for 5-minute animated works and dislikes anything over 20 minutes long) and too serious topics. Besides that, he advises young fellow animators to draw all the time, be disciplined enough to never stop working hard ti improve their abilities, and be passionate enough about their work to always push forward.

"A lot of my mistakes in drawing make a much more interesting film."

Plympton continues to draw every day for a couple of hours, but doesn’t want to use computers, since working on them is too expensive and time consuming. Therefore every outline, storyboard and layout are done by hand.

“[Sometimes] the perspective is maybe a little wrong, a little skewered, but that‘s what makes it cool. […] In fact this is something that I really believe in, that a lot of my mistakes in drawing make a much more interesting film. That‘s one reason I don‘t like Pixar, everything is perfect. I like the feeling of imperfection, the feeling of drawing with an imperfect hand.”

With this in mind, it is no surprise that he liked the technically imperfect works from Egon Schiele that he saw during his visit in Vienna. When asked about his other influences or work he admires, he cites another Austrian-born film-maker, Billy Wilder, alongside Tex Avery, Robert Crumb, Frank Capra, Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy…

Plympton runs his own studio.

Plympton runs his own studio, in which usually six to ten people are working on projects. The studio finances itself through theatrical (cinemas) as well as non-theatrical sales (for example schools, libraries, institutions, airplanes – and of course TV), DVDs, internet (Video on Demand), merchandise (books, posters and other artwork), commissions (commercials for Volkswagen, MTV, music videos for Madonna, Kanye West, animations for documentary films), appearances (lectures and masterclasses at schools or festivals) and since recently also through Kickstarter campaigns.

Working for the studio helped several artists to build their own careers. Good examples are Signe Baumane, who went from starting as a colorist for Plympton to becoming one of the leading female animators today (recently Rocks in my pockets), and Chris Miller, who in Plympton’s view became a Hollywood mogul by directing the remake of 21 Jump Street and The Lego Movie among others.

"As an artist, you really don´t want to be politically correct."

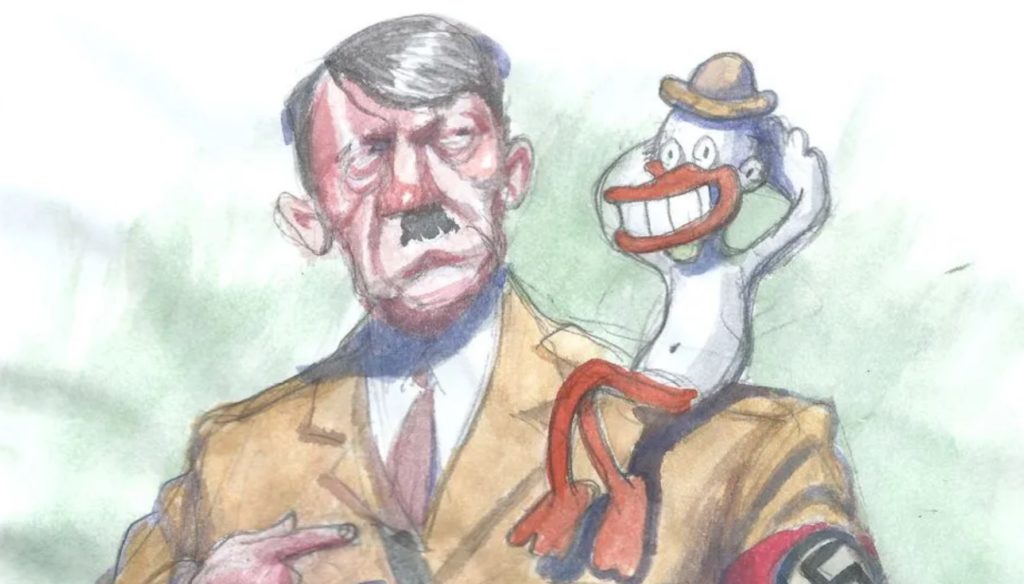

But there is also the opposite case, people who leave the studio because of creative differences. Recently this happened during the development of his next feature film, the mockumentary Hitler’s Folly. In it Plympton plays with the idea that Hitler gets accepted in the art academy, becomes a cartoonist and runs his own studio. Being a self-proclaimed World War II nerd, Plympton was inspired by the fact that such an evil person as Hitler fell in love with Disney’sSnow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The provocative film premiered on the 1st of June in New York and a free stream of it is available online on the 3rd of June on his website, “as special thank you to his loyal fans”.

Plympton knows it might have been smarter to not make this film, but he thinks the idea is funny and hopes that the audiences will also see it this way:

“Political correctness has its place, but that is not something that I want to do. As an artist, you really don’t want to be politically correct, because you want to inspire people or shake people up or get people thinking differently and see the other side of the story.”

He wants to change the Hollywood notion that short films are only good to open doors to a three-picture-deal.

Although he is constantly trying to prove otherwise, his many animated short films are his most successful works. As he said, his live action films were neither popular nor profitable. And we will see how his latest attempt at feature films will go, but the ironic fact is that he sometimes had to support his previous seven feature films by producing and selling short excerpts from them as individual short films. In the end, those excerpts were again more successful than the film as a whole. A good example for this is The Tune, which he got to the Sundance festival over selling one segment (The Wiseman) for heavy rotation to MTV and other TV stations, and winning the Jury Prize at the Cannes festival with another segment (Push Comes to Shove).

Speaking in general, Plympton asserted that he will continue to fight for short films, especially in his own country. He wants to change the Hollywood notion that short films are only good to open doors to a three-picture-deal at a studio and show that the form is much more, often wonderful and powerful artworks in their own right. And he wants to shift the perception of American audiences to a more European one and convince them to finally really accept adult topics in animated films.

All the best, Bill, and thanks for the laughs!

first published in Nisimazine, 06/2016