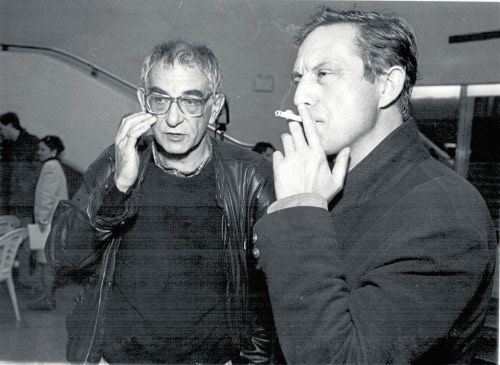

When we think of Polish cinema, at least three directors come to mind: Roman Polanski, Andrzej Wajda and Krzysztof Kieślowski. The latter would have turned 75 this year, and at the same time it is 20 years since his sudden death. In a year without their main festival (the next one will take place in March 2017), Let's CEE, Vienna´s festival of Central and Eastern European cinema, decided to organise a retrospective including, among others, Kieślowski's major hits: The Double Life of Veronica (1991), Dekalog (better: A Short Film About Love and A Short Film About Killing, both 1988) and the Three Colours trilogy (1993-1994). I spoke to his long-time co-screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz about the director and other topics. The smooth 70-year-old, who was also nominated for an Oscar for Best Screenplay in 1995, answered my questions with the same level of cleverness that he still uses when writing film proposals.

"One day he remarked that we both came from the documentary field: he from documentary filmmaking and I from the courtroom."

You studied law, worked as a lawyer, were a Member of Parliament and somewhere in between became a screenwriter. Which of these fields is your greatest passion?

Krzysztof Piesiewicz: When I was about 30 years old, the situation in Poland at that time allowed me to help people who had chosen to do what I called “soft heroics”. As a lawyer, I represented them in the biggest political trials during the communist dictatorship. I was very young, spontaneous and I did everything I could to give my clients hope. But later I paid a high price for my work. Despite that, I think it was the most beautiful period of my life. That´s when my personality was formed. But I’ve always been very interdisciplinary, I’ve been interested in many things. I think it was inevitable that I met Kieślowski. At that time, I was known as a young and promising lawyer, and he as a young and talented director. When we met, we started to observe each other very closely. I did most of the talking, and he was watching me. Then one day he remarked that we both came from the documentary field: he from documentary filmmaking and I from the courtroom.

What was the working process like? Who was responsible for which part of the screenplays?

In all the films we have made together, I have been the one who has contributed ideas about the story and the protagonists. I have the feeling that Kieślowski saw me as an actor in one of his documentaries at that time. Suddenly, a young man came into his life who had a clear idea of the world, but at the same time was a little childish, naïve, and idealistic. I think that in the first years of our acquaintance he saw me as both subject and object. Only then did he gradually draw me deeper and deeper into his world.

"An artist must be able to recognize evil, but also to see the good and the beautiful."

In recent years, other directors such as Tom Tykwer and Danis Tanović have made films based on your screenplays. What do you think of these films?

I am very pleased with my collaboration with Tykwer (Heaven, 2002). I think the result is a very genuine, beautiful, emotional, and well-made film. But unfortunately, with its premise of understanding terrorists, it came at the wrong time. Nevertheless, I consider this film to be very important, both in general and in my career. Tanović, on the other hand, proved to be very temperamental, which is neither good nor bad. I think he has managed to make a very interesting film (L’Enfer, 2005), although I would have liked to have cut it down a little.

I have worked as a screenwriter on about 20 films so far. I have always come across wonderful directors and actors. And I’ve managed not to make a fool of myself on any of these projects. But working with Kieślowski was unrepeatable. We worked together all the time, from the first word of the script to the last cut in the editing room. The other members of the crew were also always following us and constantly bringing in their own concepts for the camera, the music, etc. But that’s not unusual in film history. There have been artistic teams elsewhere, too, for example in Italian cinema, which used to be considered the best in the world.

Poland recently won its first Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, while at the same time experiencing major political turmoil. How do you see the current state of Polish cinema?

In my opinion, there are many talented people, but they do not describe what is important: the world in which we live. But this is not just a Polish problem. A huge number of films are being produced, but that does not mean that they are of good quality. Also, films nowadays focus too much on evil, brutality and dysfunctionality. Instead of looking for what people need: light. These films divide people instead of bringing them together. Some Polish directors, for example, survived the Second World War and witnessed the Holocaust, but still managed to make films about love in a concentration camp. An artist must be able to recognize evil, but also to see the good and the beautiful, otherwise he is committing a sin. He must believe in human beings.

"Sometimes the foundation of a great story emerges from a single close look."

Your films are based on “ideologies” such as the ideals of the French Revolution, the Ten Commandments, etc. Is there a methodology behind this to aid the writing or some other reason?

I came up with the idea for the Three Colours trilogy in 1989, when many good things were happening in Europe, but I still felt uncomfortable about the developments. In these films I never dealt with the ideas themselves, but with their impact on people. I did the same with The Decalogue, which is not a series of theological films at all, but a series of psychological dramas. The focus has always been on trying to describe certain civilization-driven ideas by means of certain psychological processes. But there is also a desire for the films to touch the audience, to awaken emotions. That is the most important thing.

What advice would you give to young screenwriters?

It is necessary to rethink your message, to be compassionate about the subject matter, but above all it is important to be constantly observant. Sometimes the foundation of a great story emerges from a single close look. A scriptwriter needs to know the structure of scripts, but the key skill is the ability to think in pictures. A group of words form sentences which must be turned into pictures. Anyone who cannot do this will not write a good script.

first published in Slovenian in Koridor, 10/2016