A small gem about the gifts of wonder, curiosity, profound observation, reflection and creativity.

Now we grieve cause now is gone

Things were good when we were young

Is it safe to say, c’mon, c’mon

Was it right to leave, c’mon, c’mon

Will I ever learn, c’mon, c’mon

C´mon, c´mon, c´mon, c´mon, c´mon

(The Von Bondies, C´Mon C´Mon)

Quite a few years ago, when I was finishing my studies, I met up with a former classmate from high school. During a walk, she asked me, like a bolt from the blue, one of those classic, basically very simple, but wretchedly difficult questions: “Are you happy?” I automatically rushed to answer the monologue I had learnt: how I still had to tick off this and that, but when I did, I was sure I would actually be happy. After all, happiness is defined only through a degree, a job, a salary and similar status symbols, isn’t it? Far too often – albeit for obvious reasons – we as adults think in similar mechanical terms, and because of the ubiquitous noise of everyday life, we lose what we had as children: the gifts of wonder, curiosity, profound observation, reflection and creativity.

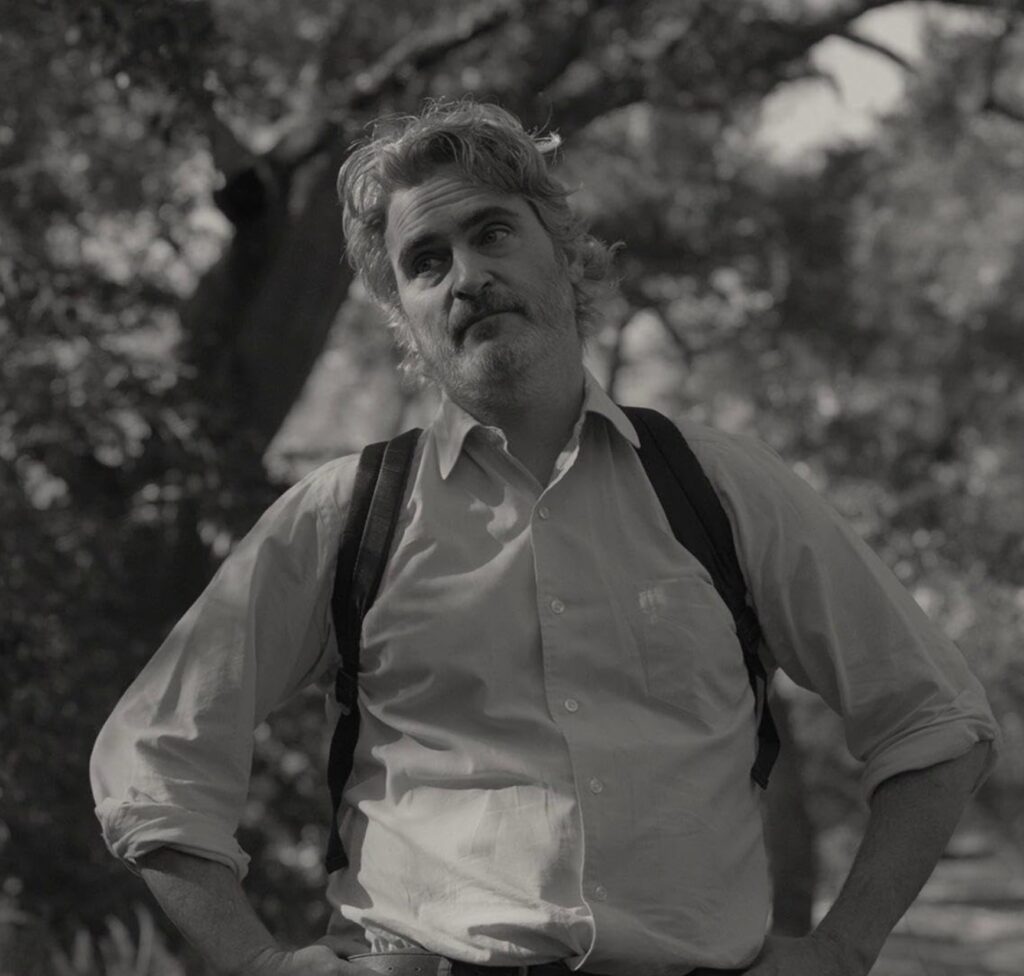

Phoenix´s role here couldn´t be more opposite to his role in Joker

Similar issues are raised (not only) by children in the film Come On Come On, which had its world premiere at the Telluride Film Festival last year and then completely faded into obscurity for reasons that remain unexplained. Even though the film is the brainchild of director and screenwriter Mike Mills, who has already wowed us in the past with his highly personal, exquisitely written dramas Beginners (2010) and 20th Century Women (2016), the latter of which earned him, among other things, an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay. In addition, Come on Come on is the first feature film starring Joaquin Phoenix since his well-deserved triumph at the Oscars. It is true, however, that his role in this film could not be more opposite to the now iconic role of Arthur Fleck in Joker (2019, Todd Philips).

Phoenix plays Johnny, a moody and sensitive radio journalist who travels around the US with his team, interviewing children and adolescents about their views on themselves and their surroundings. During the tour, which in the film covers Detroit, Los Angeles and New Orleans, his private life catches up with him. Illness resurfaces in his family. In flashback, we learn that Johnny and his sister (Gaby Hoffmann) were coping with their mother’s dying years ago, but this time, the mental illness symptoms of his sister’s partner (Scott McNairy) reappear. So Johnny decides to help his sister and temporarily take over the care of his nephew (Woody Norman).

C´mon C´mon is primarily a therapeutic film

Come On Come On is one of those silent films that are the opposite of our modern times when most people scream unnecessarily, and those who should cry for emotional cleansing keep their thoughts to themselves. If we remove the classical narrative element of the journey, the whole film is introspective. True, the characters change throughout the film. Still, the conflicts they become embroiled in are in fact only within themselves, provoked by the very conversations between the protagonists (professional actors) and the documentary interviews with the children and adolescents. For this reason, Come On Come On is primarily a therapeutic film, with much discussion of concepts such as happiness, fear, loneliness, the future, the nature of memory, family and the recognition of mistakes and weaknesses, but it also indirectly addresses the need for escapism and catharsis. Surprisingly, it turns out that children are more in touch with themselves than adults, who often hide behind some carefully constructed facade of external images. Children’s directness opens up the pores of adult personalities and reveals their inability to answer life’s questions truthfully. After all, it is easier to ask them than to be challenged to give an honest opinion of one’s own.

"Over the years, you will try to make sense of that happy, sad, full, empty, always-shifting life you're in. And when the time comes to return to your star, it may be hard to say goodbye to that strangely beautiful world."

All these conversations are formally presented in an essentially linear form, except for a few inserted montage elements where the film goes back in time or rushes the sound before the image. The use of book quotations, for example, is interesting. These are introduced by title and author but are fragmented throughout the narrative, commenting on and complementing the action. They range from essays by psychotherapist Andrea Nair (A How-To Guide to Parent-Child Relationship) and director of photography Kirsten Johnson (An Incomplete List of What The Cameraperson Enables) to children’s books by L. Frank Baum (The Wizard of Oz) and Claire A. Nivola. Given that part of the latter text brings Johnny to tears in the film, it is worth writing an excerpt here:

“Over the years, you will try to make sense of that happy, sad, full, empty, always-shifting life you’re in. And when the time comes to return to your star, it may be hard to say goodbye to that strangely beautiful world.” (Claire A. Nivola: Star Child)

Particular attention is paid to the individual´s facial expressions and emotional states

On the visual level, the only colour part that really stands out is the dedication at the end of the film to one of the children interviewed, Devante Bryant, a nine-year-old boy who was the victim of a shooting shortly after the filming. The rest of the film is in black and white, with an intensity similar to that of the masters of photography, such as Vivian Maier or Henri Cartier-Bresson. Particular attention is paid to the individual’s facial expressions and emotional states to the extent that the whole film, not just the interviews, takes on a documentary feel. Joaquin Phoenix’s personal crossroads and his use of recording equipment to hunt down sound bites of real life are a bit reminiscent of Rüdiger Vogler in Wim Wenders’ Lisbon Story (1994).

"Whatever you planned on happening, that doesn't happen. Other stuff you never thought of happens. So just - c´mon.."

But the real star of Come On Come On is 13-year-old British actor Woody Norman, who also received a BAFTA nomination for Best Supporting Actor for his role. No doubt we can predict a bright future for him. With his expressive performance, he manages to play both the anger and helplessness as well as the playfulness and naivety of a child, all complemented by an orphan’s alter ego and introspective moments. By mirroring the behaviour of adults, he has seemingly become almost more adult than the adults themselves – though, of course, he continues to demand attention and protection from them. Norman’s character of Jesse is also the one who provides the film’s summary and leitmotiv:

Whatever you planned on happening, that doesn’t happen. Other stuff you never thought of happens.

So just – c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon …

A bittersweet and sincere film

Come On Come On is a small, bittersweet, sincere and very life-affirming film that shows us that we must repeatedly try to bring out the child in ourselves and change how we look at problems. Maybe with more distance, maybe with more naivety. But certainly with less pretence and more directness concerning ourselves and others.

first published in Slovenian language at Koridor