The final film of Andrzej Wajda, one of the most political Polish directors, world-premiered in September 2016 at Toronto, just a month before his death.

Afterimage follows the last years of the Polish constructivist painter, professor and art theoretician Władysław Strzemiński.

The title of the film comes from his term for the trace of an object with the same shape but the opposite colour that remains in front of our eyes after we stop looking at it.

The period between 1948 and Strzemiński’s death in 1952 was marked by the conflict he had with the pro-Soviet regime in Poland. For the government no neutral art existed as they pushed to establish socialist realism, which they presented as closer to the people and working moral, as well as more useful for the ideology than the »imperialistic« modern art.

Every authoritarian regime has its own »degenerate art«. Strzemiński opposed that and fought for the possibility of a free and wider approach. The reaction of the state was a variation on »damnatio memoriae«.

His only passion was art.

While in ancient Rome mostly opposing politicians were condemned, in modern times it was further extended to artists, considered apolitical, insurgent or subversive. The basic principle remained the same: every trace of a person had to be destroyed, never to be remembered again.

Despite this struggle, Strzemiński, convincingly played by Wajda regular Boguslaw Linda, remained a strong personality, who could be neither pressured nor persuaded to join the regime. Still he remained detached from his caring family and worshiping students. His only passion was art. It is just a pity that the director decided to not present more of Strzemiński’s work, instead of the meticulously shown pieces by his students and his wife, the sculptor Katarzyna Kobro.

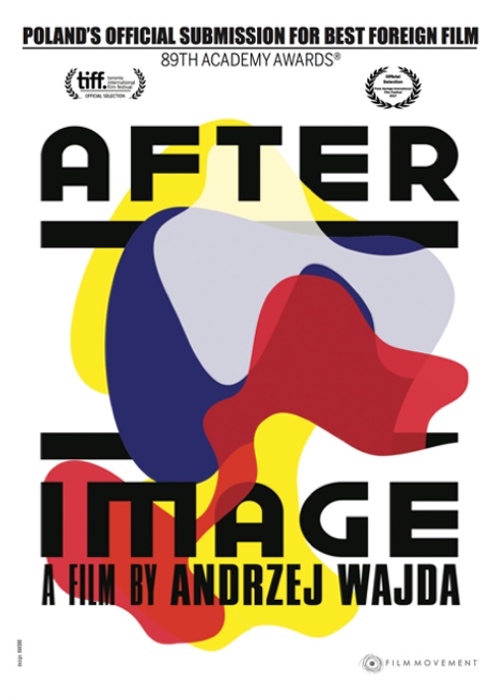

The film – also the Polish entry for the best foreign language film at the next Academy Awards – repeats the director’s regular motive of an individual fighting against a powerful regime, like in Walesa: Man of Hope (2013), Danton (1983) and Man of Marble (1977).

The viewer is confronted with some striking contrasts and Wajda's confident use of stunning visual details.

It is maybe a too-conventional drama for its avant-garde subject matter and it is shot in predominantly brownish and grayish tones, so often used in the portrayal of the so-called dull socialist everyday life. But the viewer is confronted with some striking contrasts and Wajda’s confident use of stunning visual details.

One example are body parts of mannequins, dangling around in a window display, which gets another layer of meaning considering that Strzemiński lost an arm and a leg in the First World War. Another is the pivotal moment, in which while the protagonist is painting, workers erect a huge Stalin banner in front of his window and his canvas turns red. His reaction starts the confrontation with the regime that will finally lead to his death.

Wajda once again condemned ideology and the restrictions of freedom it causes.

Whenever film directors make an artist biopic, one can’t help but look for reflections of the film-maker in the portrayed artist. Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner (2014), for example, was the director’s inquiry of the role of a successful older artist in the society. It comes as no surprise that Wajda, himself a victim of the Stalinist regime, in his swan song summed up his convictions and once again condemned ideology and the restrictions of freedom it causes.